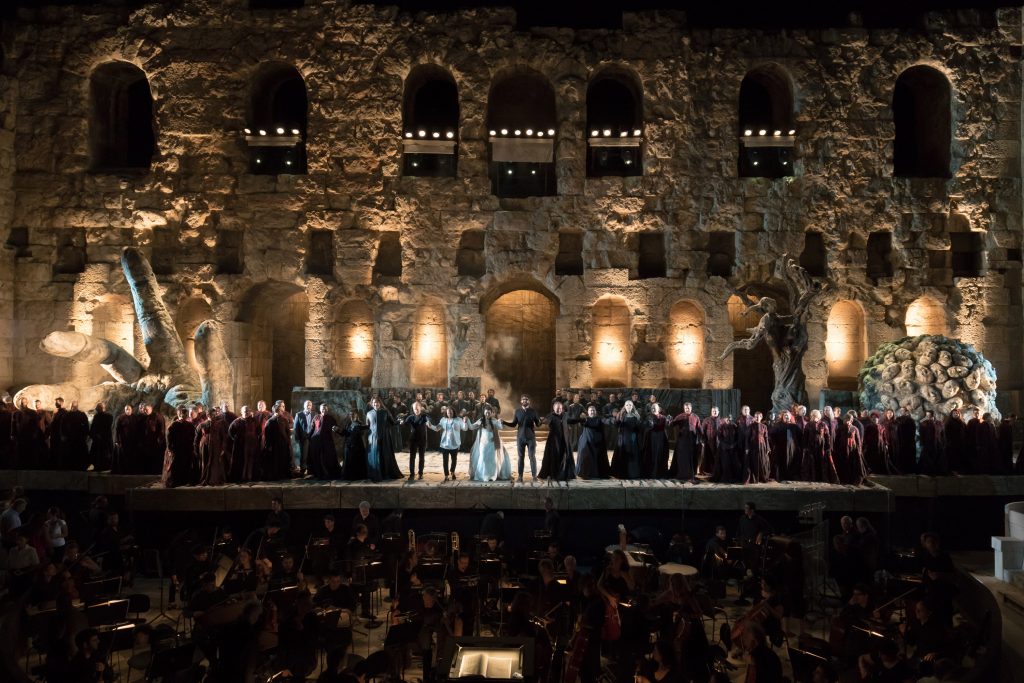

In fifty years of opera-going, I have never been to a performance of Il Trovatore without anvils. Deprived of their tools and metal-ware, the poor gypsies were forced to mime a Swedish Drill during the so-called Anvil Chorus, with punching arms and swinging shoulders. This lapse and alteration to the score was symptomatic of an approach by the producer, full of ideas, but few appropriate to this notoriously difficult opera. Trovatore works best when performed at white heat, with a production to match. The mixture of public and private scenes, great choral moments, meltingly beautiful and stirring arias should be fast-paced and contrasting. It was not just the limitations of the long, shallow stage which impeded this, but the inability of the producer to come to terms with Verdi and Cammarano’s conception. The result was a disappointing evening, though in majestic surroundings.

The wide stage was cluttered with several intruding objects including a large open hand standing in one of the two shallow pools at each side. Hands were a motif of the production. In Act 3, the soldiers apprehended Azucena with hands on long poles, which they swung rhythmically from side to side to unwitting comic effect. The leading characters and chorus tripped through the pools, dampening their trailing robes. Leonora delivered “Di te! di te! scordarmi”, distractingly recumbent in the water, splashing it with her hands in frustration. One hopes at least it was warm. At moments the action was enlivened by tableaux vivants: a group of male actors re-enacting The Raft of the Medusa with writhing semi-naked bodies in Act II; or a solitary, spot-lit bloodied torture victim writhing in torment at the side of the stage during Act IV.

Elsewhere, slow processions were the order of the evening: Luna’s entourage in black leather; gypsies, in black splashed with scarlet, and soldiers clad in black, with black flags and pointed hoods in Act IV. The ponderous tread of their slow departure dragged into the ensuing scene, no matter how heart-wrenching or intimate. The costumes swished noisily over uneven, faux-flagged flooring, which caused problems of mobility for singers and chorus alike throughout the evening.

Things were mostly better musically. Enrico Caruso remarked that all the opera required was the four greatest singers in the world. This was achieved at least in part by the splendid singing of Dimitri Platanias as Luna who was by far and away the most impressive of the main characters. He has a warm, responsive voice which makes me look forward to his appearances in the Royal Opera House,London, later in the year and next. But with only basic acting skills and little in the way of movement he tended to stand, deliver and depart. The Azucena of Elena Manistina seemed to gain confidence after “Stride la vampa” and was effective and moving thereafter. Cellia Costea was similarly so as Leonora, adding a few embellishments here and there and was secure as well as moving at the top of her range. Manrico (Walter Fraccaro), mature in years, added a new incongruity to the plot. Could he really be younger than his supposed mother? He sang solidly and well and was at times thrilling.

The chorus was disappointing, with ragged entries and often tentative singing in passages which should normally blow the audience’s socks off. There was a vast improvement in the off-stage “Miserere” where the musical director was able to take more charge. Miltos Logiadis the conductor did not impress: tempi were ponderous, with pedestrian, often tired orchestral playing, particularly in the third and fourth acts. There were some ensemble issues, the orchestra at times overwhelming the singers. Bring back the anvils, say I.

Stephen Roe,

Limnionas,

Samos,

July 2017